User space traffic shaping with Ruby

Download Netwatch-1.0.zip.

In my Kernel space traffic shaping with Linux post, I came to the conclusion that none of the traffic shaping algorithms within the Linux kernel was suitable for my needs. The effects of running the traffic shaping algorithms were too hard to quantify and coming up with the right set of parameters to go with each algorithm was challenging.

So I decided to come up with my own shaping algorithm, running in user space because it’s simpler working from there. I also wanted to use Ruby to learn the language and because of Ruby’s good properties as an integration platform. Lastly, I wanted the shaper to perform deferred shaping based on the traffic patterns observed over a period of hours or days rather than the more or less immediate shaping carried out by the kernel-based algorithms.

Before getting into the details, I should mention that these concepts have been successfully applied to shaping traffic on our 100/100 mbps Internet connection, shared by some 330 apartments, for well over a year. We’re no longer experiencing issues with network congestion and now that we use a payload agnostic shaper, we no longer have to combat the ever more sophisticated attempts of P2P software to camouflage its traffic.

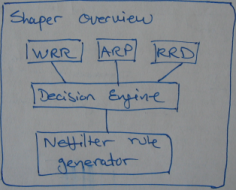

Architectural overview

At an overview level the shaper is composed into a number of subsystems. At the top are the WRR scheduler, the ARP cache, and the RRD database system that retrieve and store metadata information about computers and their traffic.

Based on input from these subsystems, the shaper’s decision engine evaluates each computer’s bandwidth usage against a set of rules. Should at least one rule be violated, e.g., too much traffic over some defined period of time, the shaper calls out to another subsystem that determines how to handle the violation. In this case Netfilter is called upon to take action, blocking the computer from accessing the Internet and redirecting it to an information page.

Weighted Round Robin scheduler

Within the shaper, kernel and user space form a symbiosis through the WRR scheduler. As part of WRR’s inner workings, the scheduler counts the bytes transmitted on a per IP basis. So although we don’t use WRR for shaping, per say, we do use it to track the byte counters of each computer.

Getting WRR to reveal this information is done through the tc (for traffic control) command. As outlined in the Kernel space traffic shaping with Linux post, only outgoing traffic can be shaped by WRR (any algorithm really). Hence, tc is called once for eth0 and once for eth1, and parsing the result, we know have much traffic has entered and exited each computer between this and the previous call to tc.

For each computer the output has the form below. Of particular interest are the address and the bytes fields:

% tc class show dev eth0 class wrr 8001:1fb parent 8001: (address: 192.168.1.231) (total weight: 0.872749) (current position: 4) (counters: 1 2 : 3 4) Pars 1: (weight 0.872749) (decr: 1e-10) (incr: 7.5e-11) (min: 0.1) (max: 1) Pars 2: (weight 1) (decr: 0) (incr: 0) (min: 1) (max: 1) bytes: 4546184) (packets: 55373) ...

The address is dynamically assigned through DHCP and is therefore subject to change. Also, the byte counters aren’t retained across restarts, so we need to draw on additional subsystems to align the WRR output with a computer’s unique identity across time.

Address Resolution Protocol

In a DHCP based environment the IP address of a machine may change over time. So to ensure that traffic is always attributed to the correct physical machine, the WRR byte counters aren’t tied directly to the IP address when stored. Instead, we use the ARP cache to look up the corresponding MAC address, which is assumed to be static.

This lookup is done by maintaining an in-memory set of IP/MAC mappings, populated by parsing the output of the ip command:

% ip neigh 192.168.1.231 dev eth1 lladdr 00:50:8d:68:50:75 REACHABLE 192.168.3.117 dev eth1 lladdr 00:11:d8:8f:0e:3b REACHABLE ...

Thus, combining WRR with ARP, the shaper is able to associate byte counters with the MAC addresses of LAN-connected computers. Restarting the machine, the shaper, or Netfilter, however, will still cause traffic shaping data accumulated over time to be lost.

Round Robin Databases

We could’ve opted for persistence to a text file, a hierarchical XML structure, or a relational database, but time series data doesn’t lend itself well to these traditional approaches — at least not without preprocessing. Because with time series data, such as the 32 bit integer byte counters for each computer, counter-wrap is a frequent event (occurs every 4GB of transferred data). And restarting the machine, the shaper, or Netfilter is also a common event that’ll most likely cause an outlier to be recorded because all counters are reset.

Logic for making sure these events doesn’t pollute our database with erroneous measurements are part of the defining characteristics of a time series database system. In addition, querying data, such as summing within a period of time and making sure the sum isn’t affected by the above events, is what a time series database is good at.

On Linux-based based systems, Tobias Oetiker’s Round Robin Database tools are the de facto tools for storing, querying, and graphing time series data, and therefore the ones used by the shaper.

The idea is that, using the RRD tools, each computer gets its own database, named after the corresponding MAC address, describing its traffic over time. So querying the database of each computer can tell us how much data was transferred and received over some period of time. Using the RRD tools for this task eliminating the need on our behalf to deal with outliers, missing values, counter-wraps, and so forth. All the shaper has to do is record the value of the counters at regular intervals and RRD makes sure data is consistent within the database.

Decision engine

To put the shaper online, it’s run from a Bash script containing an infinite loop that (1) reads and parses the WRR output, (2) reads and parses the ARP cache entries, (3) writes the byte counters to the RRD databases, (4) uses the RRD querying tool to sum the data based on the rules specified, possibly causing a violation event to fire, and finally (5) goto sleep for some period of time before starting all over.

Whenever a rule is violated, the action taken may be whatever can be expressed though Ruby code or through a callout. This may involve sending an email to the network administrator or disabling Internet access for the computer in question.

Within our configuration, we defined a set of rules that state that within a four hour sliding window a computer is allowed to upload no more than 5GB and download 10GB of data. Similarly, during a seven day sliding window, a computer is allowed to upload no more than 30GB and download 60GB of data (the exact quotas and periods obviously depend on the network capacity, users online, their usage patterns, and so forth).

Upon violation of a rule, we employ Netfilter to redirect a computer to an information page stating that the computer is blocked from accessing the Internet in conjunction with the sum of the four hour and seven day totals.

Conclusion

Observing the proof of concept shaper in action, the biggest problem seems to be that a few users modify their MAC address to get a bigger piece of the bandwidth pie. If we wanted, though, changing the MAC can be counteracted by introducing another layer, and instead tie traffic to the port on the switch to which the computer is connected.

As far as the available source code goes, it should probably only be used as a starting point for building your own system.