Strongly typed SharePoint list operations using the repository pattern

This post is part of series:

Part 4 – Strongly typed SharePoint list operations using the repository pattern in F#

Part 3 – Bringing together repository and tree structure in business layer

Part 2 – Creating and working with a custom tree data structure in C#

Part 1 – Strongly typed SharePoint list operations using the repository pattern

I first wrote about accessing SharePoint lists using the repository pattern about three years ago. Since then I’ve reused that approach, with a few improvements, on almost every SharePoint project I’ve worked on. The improvements include generating CAML queries using LINQ to XML, taking a more functional approach to mapping from loosely typed to strongly typed data, passing in more specific arguments, not tying the repository to a definition class, and removing assertions to focus more on validating user rather than developer input.

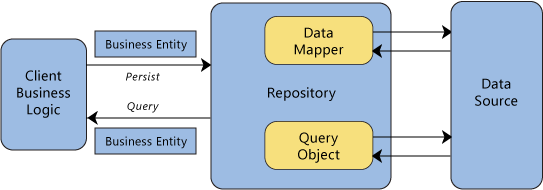

Depicted graphically, here's what I want my repository to do, albeit in a less sophisticated way than the SharePoint guidance by the Patterns & Practices team:

As an example, suppose I have a SharePoint list containing the internal fields below. Accessing field values through the SPListItem.Item property yields results of type object, which may then be cast to the type of the input type column. For some fields, such as Location_Legal and Url, I not only want to project it onto a differently named field but also a different type as indicted by the Output type column. The type may be changed to one that is more precise and/or easier to work with, given the client’s requirements. As a final note, observe how the internal names are inconsistently named. The repository can help bring some order to the naming and type chaos:

|

Internal name |

Strongly typed name | Input type |

Output type |

|---|---|---|---|

| LinkFilename | Title | string | string |

| _ModerationStatus | ApprovalStatus | string | string |

| Location_Legal | Locations | TaxonomyFieldValueCollection | IList<string> |

| ProcessHierarchyLevel | Level | string | int |

| Url | Url | string | Uri |

| ProcessHierarchyLegal | ProcessHierarchy | TaxonomyFieldValueCollection | IDictionary<Guid, string> |

| _dlc_DocId | DocumentId | string | string |

| Parent Document Id | ParentDocumentId | string | string |

Here’s an example of a simple repository with read operations only. It’s easily extended with create, update, and delete operations. Don’t pay too much attention to the concrete fields. They’re meant as examples:

public class LegalDocument {

public string Title;

public string ApprovalStatus;

public IList<string> Locations;

public int Level;

public Uri Url;

public IDictionary<Guid, string> ProcessHierarchy;

public string DocumentId;

public string ParentDocumentId;

}

public class LegalDocumentRepository {

const string LinkFilename = "LinkFilename";

const string FileLeafRef = "FileLeafRef";

const string ModerationStatus = "_ModerationStatus";

const string Location = "Location_Legal";

const string ProcessHierarchyLevel = "ProcessHierarchyLevel";

const string ProcessHierarchyLegal = "ProcessHierarchyLegal";

const string DocumentId = "_dlc_DocId";

const string ParentDocumentId = "Parent_x0020_Document_x0020_Id";

protected SPListItemCollection Query(SPList list, XElement caml) {

var query = new SPQuery {

Query = caml.ToString(),

ViewFields = new[] {

LinkFilename,

ModerationStatus,

Location,

ProcessHierarchyLevel,

ProcessHierarchyLegal,

DocumentId,

ParentDocumentId }

.Aggregate("", (acc, fld) =>

acc + (new XElement("FieldRef", new XAttribute("Name", fld)).ToString())),

ViewAttributes = @"Scope=""RecursiveAll"""

};

var result = list.GetItems(query);

return result;

}

public LegalDocument GetByFilename(SPList list, string filename) {

var caml =

new XElement("Where",

new XElement("Eq",

new XElement("FieldRef", new XAttribute("Name", FileLeafRef)),

new XElement("Value", new XAttribute("Type", "Text"), filename)));

var result = Query(list, caml);

return Map(result).Single();

}

public IEnumerable<LegalDocument> GetApprovedDocuments(SPList list) {

var caml =

new XElement("Where",

new XElement("Eq",

new XElement("FieldRef", new XAttribute("Name", ModerationStatus)),

new XElement("Value", new XAttribute("Type", "ModStat"), "Approved")));

var result = Query(list, caml);

return Map(result);

}

private IEnumerable<LegalDocument> Map(SPListItemCollection items) {

Func<object, int> levelMapper = o => {

var s = (string) o;

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(s))

return 0;

var v = s.Split(new[] { ':' });

return v.Length == 0 ? 0 : int.Parse(v[0]);

};

Func<object, IList<string>> locationMapper = o => {

var t = (TaxonomyFieldValueCollection) o;

return t.Select(f => f.Label).ToList();

};

Func<object, IDictionary<Guid, string>> processHierarchyMapper = o => {

var t = (TaxonomyFieldValueCollection) o;

var kvp = new Dictionary<Guid, string>();

t.ForEach(f => kvp.Add(new Guid(f.TermGuid), f.Label));

return kvp;

};

Func<object, string> parentDocumentId = o => {

var s = (string)o;

return string.IsNullOrEmpty(s) ? "" : s.Trim();

};

var urlPrefix = items.List.ParentWeb.Url + "/";

var documents =

from SPListItem i in items

select new LegalDocument {

Title = (string) i[LinkFilename],

ApprovalStatus = (string) i[ModerationStatus],

Locations = locationMapper(i[Location]),

Level = levelMapper(i[ProcessHierarchyLevel]),

ProcessHierarchy = processHierarchyMapper(i[ProcessHierarchyLegal]),

DocumentId = (string) i[DocumentId],

ParentDocumentId = parentDocumentId(i[ParentDocumentId]),

Url = new Uri(urlPrefix + i.Url)

};

return documents;

}

}

The repository code has a number of interesting points to be aware of:

- Only include the fields required by the client in the CAML query. Extra fields will have a negative impact on mapping performance and creates a high coupling between the repository and the SharePoint list. This coupling may prevent future updates to fields without updating and re-deploying the repository as well.

- Calling SPList.GetItems() only takes a few milliseconds. The expensive part is materializing the result collection. Replacing the call with one to SPList.GetDataTable() doesn’t change anything, except that now the repository's Query method, rather than the Map method, is where the majority of the execution time is spent.

- Each of the repository access methods, such as GetApprovedDocuments, accepts a SPList instance. The calling code must take of getting hold of an appropriate SPList instance. In case a repository method require access to the list's parent SPWeb or SPSite instance, they’re available through the SPList instance.

- The LINQ to XML code is more verbose than the equivalent string representation of a CAML query, but prevents certain types of syntax errors from creeping into the query. Complex structures, strings in this case, should generally be constructed by a builder that encapsulates the details of the structure.

- Whether to create many smaller repositories or a large one that combines all the operations on a list is a matter of taste and general application architecture. Maybe the architecture consists of multiple bounded context in which case multiple repositories would make sense.

- The mapping within the Map method is lazy. Only when the client enumerates the collection, or calls ToList() on it to force immediate query evaluation, does the mapping of each item take place. Depending on how you plan to use the repository, it may or may not make sense to return an lazily evaluated collection.

- Unit testing code that makes use of a repository becomes simpler. The repository can implement an interface through which your clients access it, enabling you to inject a fake repository into your business logic. Alternatively, your mocking framework may be capable of mocking a concrete class.

- LINQ to SharePoint could be used as an alternative to writing CAML queries by hand. I've refrained from using it because I think it adds unnecessary complexity and no value to the solution.

With this simple repository abstraction, I’ve created a data access layer that the business layer can call into and get back objects and collections of objects almost as if they're in-memory objects, hiding away most of the SharePoint data access intricacies.