Computer activation with ASP.NET MVC

Download source or watch demo.

(Other posts in this series include: Kernel space traffic shaping with Linux and User space traffic shaping with Ruby that touch exclusively on Linux issues.)

This post covers an Asp.Net MVC application (for an overview of Asp.Net MVC, the Herding Code guys recently interviewed Phil Haack) I wrote that automates the collection of information about computers and their owners on a local area network. The idea is to have the Internet gateway match the identity of each computer that wants to send traffic through it against a white list. Should the request originate from an unknown computer, the gateway redirects that computer to a web application for Internet access activation. Each user then has to create an account and provide verifiable contact information and/or associate their computer with an existing account.

With the contact information of every connected user, maintaining a network with 331 connected apartments, 371 users, and 513 privately owned computers becomes more manageable. Now you can easily email all users about general issues or individual users about specific issues, such as wireless routers exposing rogue DHCP servers or virus slowing down the network.

Without being able to contact a user, the best you can hope for is to use the MAC address to locate and disable the port on the switch to which the user is connected. But terminating network access without warning or explanation, the user has no way of knowing what hit him. Now when the user contacts you, figuring out if he’s experiencing network issues because of a closed port or something entirely different quickly becomes a challenge — and something that doesn’t scale well.

That’s where the Asp.Net MVC application comes in. To get a feel for how the software accomplishes its task, you should watch the minute and a half demo. It portrays the browsing experience of a user connecting his computer to the network for the first time and attempting to browse the web. Behind the scenes the Linux gateway uses its Netfilter capabilities to efficiently match the MAC address of each request against the white list. With no match for the computer just connected, upon browsing the web, Netfilter redirect the user’s browser to the web application. Then, every so often, using a Ruby script, the gateway queries the web server for updates to the white list and carries over the changes to Netfilter.

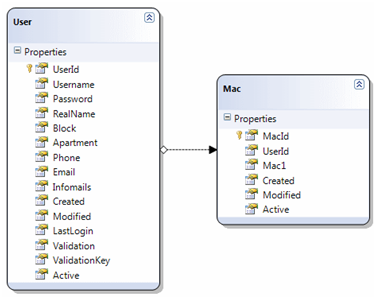

Database schema

The web application is based on the idea that a user is responsible for zero or more computers. Focusing on the web application, rather than the Linux part, the rest of this post highlights a few features that use and manipulate the data structures stored in a MS SQL Server Express database:

Reverse lookup of MAC

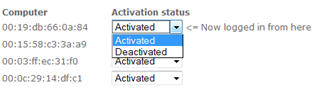

Establishing an ownership between a user and a computer is done via the MAC address of the computer. Now, it wouldn’t be particularly user friendly if the user had to go about locating the MAC address and manually typing it into a web form. Instead, the web application looks up the user’s MAC address within the ARP cache of the web server.

Because the user’s computer and the web server are both on the same local network and because they’re already exchanging data (the user is visiting a web page hosted on the server), the parties are effectively communicating through the ARP protocol of the data link layer. The data entry form is therefore able to present the user with a control that makes associating computers to the account easy. By reverse lookup, the computer currently browsing the web application is indicated by “Now logged in from here”.

Email verification

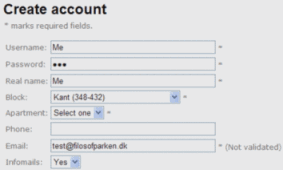

Most users don’t mind handing over basic information such as their email address. And as users are blocked from accessing the Internet, at the time of entry we only validate the email address for syntactic correctness.

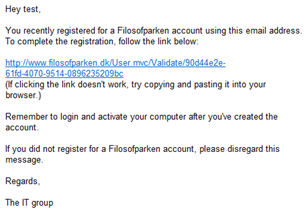

A few users, however, repeatedly entered fake email addresses to gain Internet access. Consequently, we send out an email to the address, leaving open a 24 hour window for the user to follow a link. Otherwise, the software sends out a reminder email, marks the account as inactive, and redirects the user to the web application.

Validating the syntax of email addresses is done using regular expressions. As with most complex regular expressions, they’re hard to read and verify the correctness of. They do, however, stand the test against a database of hundreds of email addresses. To come full circle, though, what is needed is a way to match the domain part of the email address against the DNS MX record of the domain. Unfortunately, MX lookup isn’t build into the .Net framework.

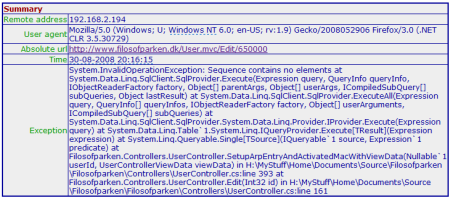

Unhalted exception emailing error handler

Error handling deserves a post on its own. Suffice it to say that to stay on top of any application, unhalted exceptions should be logged, or in this case, emailed to a designated address. Inevitably, users of your software will use it in unanticipated ways and so a global exception handler provides invaluable insight to learn from.

(Summary part of example email. Click here for complete output.)

Download and maybe try out

The web application was developed around February 2008; about the time the Asp.Net MVC framework went into Preview 2 and had started gaining momentum. Unfortunately, developing against this early a release, now the web application doesn’t run on a computer with .Net 3.5 SP1 installed.

There’s no problem compiling the application because the Preview 2 bits are in the bin folder of the application. But running the application generates an exception stating:

Could not load type 'System.Web.HttpContextWrapper2' from assembly 'System.Web.Abstractions' [located in the GAC]

That’s because the version of System.Web.Abstractions.dll that ships with .Net 3.5 SP1 no longer holds the HttpContextWrapper2 class. On a machine without .Net 3.5 SP1, however, Cassini runs the application just fine. Before running it, though, remember to create a database from the schema in Database.sql and point to that database from web.config.

Lastly, I should stress that the software is a prototype and served as a way for me to wrap my head around ASP.Net MVC and LINQ. So, the code may not win a beauty contest.

Conclusion

The activation software went online late March 2008. During the first couple of weeks I had to put in a couple of bug fixes based on what I learned from the unhalted exception emails. Since then, however, the software has served the purpose it was charged with.

The only issue that I haven’t been able to resolve is why, on rare occasions, redirecting a computer confuses its browser: if you visit a page and is redirected to the web application, for a short time after, the page keeps resolving to the web application. Most likely it’s a residual effect of the packet rewriting taking place on the gateway.

Another thing I wish I’d implemented was tracing to better understand how a couple of users got to experience a few exceptions that I don’t know how to interpret from the unhalted exception emails alone.